Why African Textiles Were Once More Valuable Than Gold

Before colonialism, mass imports, and cotton mills, a fine piece of cloth wasn’t just something you wore in many parts of Africa. It had meaning. It was power. It was status. Sometimes, it was even more prized than gold.

Clothes were used as gift and to pay debts. They didn’t just decorate, they exchanged hands. Your clothes told people where you came from, who you were and how much respect you commanded.

In this article, we will show you how African textiles became more than fabric, and why they were more valuable than gold, economically, socially, spiritually, and why people invested so much time, skill, and care into making them.

1. The Economic Role of Textile Trade

Textiles in pre-colonial Africa were serious business. Here are a few ways cloth carried economic weight:

Cloth as currency and trade good

In West Africa, merchants used textiles literally as money. Some fabrics were produced mainly for exchange, making cloth itself a recognized currency in trade.

Trade routes like the Trans-Saharan network connected forest regions and desert regions. Along with gold, salt, and ivory, textiles moved in bulk. Cloth could be traded for gold, salt, and even enslaved people. Important hubs such as Bono Manso in modern Ghana became famous for this. Merchants brought cloth, salt, and brass to trade for gold and kola nuts. Cloth travelled far and had value in many different markets.

Scarcity, craftsmanship, and demand

Good cloth wasn’t easy to make. It required skill, natural fibers or silk, dyes, looms, and long hours. The rarer the material, like imported silk or hard-to-find dyes, the higher its worth.

Some cloths were reserved for royalty or sacred events, which drove demand. For example, Kente cloth in Ghana was originally meant for kings, chiefs, and ceremonies.

Comparing value: cloth vs gold

Gold was of course highly prized everywhere. But gold was often stored away, hoarded, or used for decoration. Cloth, on the other hand, was seen, worn, and exchanged in everyday life. It had more visible and practical value.

At times, a bolt of rare cloth could cost more than small amounts of gold, especially when that cloth carried status or rarity. Cloth was also used in ceremonies, gift giving, dowry payments, and political alliances. Gold’s value was solid but less woven into daily living.

2. Social & Political Power in Cloth

African textiles were never just about covering the body. They carried weight in society, politics, and leadership. Wearing certain fabrics could instantly tell people who you were and the authority you held.

Status and hierarchy

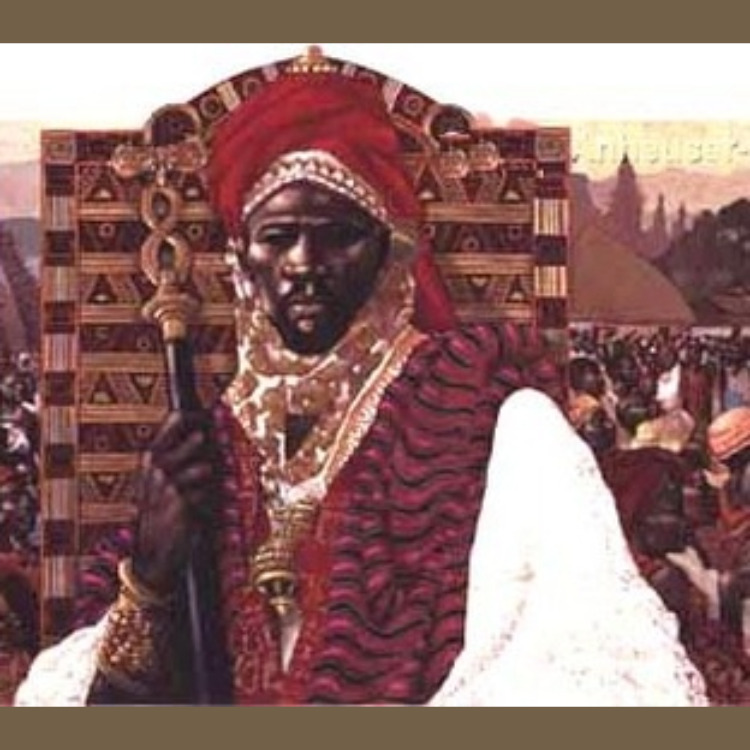

In many kingdoms, cloth was a public display of status. For example, in the Ashanti Empire, the right to wear specific Kente cloth patterns was reserved for royalty and chiefs. Each pattern wasn’t just decorative, it carried a message about rank, achievements, or even spiritual authority. Ordinary people couldn’t wear them.

The same held true in places like Yorubaland, where cloth like Aso Oke was reserved for weddings, chieftaincy, and other high ceremonies.

Politics and diplomacy in fabric

Cloth often acted as a political tool. Rulers and leaders gave textiles as gifts to secure alliances or reward loyalty. In fact, gifting textiles was a recognized form of diplomacy, much like exchanging gold or weapons.

In some regions, certain cloths were linked to power so strongly that wearing them without permission could get you punished. They functioned like badges of office. A ruler’s prestige was wrapped not just in crowns or thrones, but in the textiles, they chose to wear.

Ceremonial importance

Textiles also held ceremonial weight. For births, marriages, funerals, and festivals, fabric played a central role. The patterns and colors carried meanings that marked identity, community, or spiritual connection. For instance, among the Ewe people of Ghana and Togo, cloth was often woven with designs that told stories or represented proverbs. These designs became visual markers of culture and values.

3. Spiritual, Symbolic & Cultural Value

In many communities, a cloth was a living symbol of who you were and what you believed.

Symbols of identity and meaning

Patterns and colors carried specific messages. For example, the Adinkra cloth of Ghana used stamped symbols to represent ideas like wisdom, unity, or courage. Wearing a certain cloth allowed people to silently communicate values, lineage, or personal beliefs.

Among the Yoruba, colors in Aso Oke fabric could signal different life events, white for purity, red for power, and blue for love and peace.

Ritual and ceremonial uses

Textiles were woven into spiritual practices. In some places, certain cloths were used in burials to protect the dead, while others were worn during initiation rites to connect the living to ancestors.

For instance, bogolanfini, or mud cloth from Mali, was believed to have protective powers. Hunters wore it for safety, and women used it in life-cycle rituals like childbirth.

Oral history woven into fabric

Many cloths told stories. The Ewe Kente cloth often included patterns that told proverbs or recounted historical events. This way, textiles served as a form of non-written history, passing down lessons, warnings, and pride across generations.

Decline and Transformation

As valuable as African textiles once were, their dominance didn’t last forever. The arrival of colonial powers and the spread of industrial production changed the story of cloth across the continent.

Impact of colonialism and imports

Colonial traders and European factories flooded African markets with cheap, mass-produced cloth. This reduced the demand for handmade textiles and weakened their role in local economies. Dutch wax prints, for example, which many people today see as “African,” were introduced through colonial trade routes. They were inspired by Indonesian batik but ended up dominating African markets because they were cheaper and faster to produce.

Loss of value through industrialization

Once cloth could be made in factories abroad, the painstaking hand-weaving traditions lost some of their economic edge. Industrially produced cotton fabrics outpaced local weavers, who couldn’t match the speed or low prices. As a result, textiles that once stood as currency and treasures became less profitable.

Resilience and revival

Still, not everything disappeared. Many communities preserved weaving traditions as cultural and spiritual practices. Today, there’s a renewed appreciation for textiles as heritage and art. Designers and artists are reviving traditional styles and showcasing them on global stages. For instance, African designers using Kente, Aso Oke, and Bogolanfini have brought these fabrics into fashion weeks and haute couture collections.

Even museums like the Victoria and Albert Museum now hold major collections of African textiles, helping to preserve their history and celebrate their artistry worldwide.

Conclusion

So why were African textiles once more valuable than gold? Cloth was wealth you could see and touch. It also linked people to their ancestors, communities, and leaders.

Gold may have shone in storage or on jewelry, but textiles walked in the streets, danced at weddings, and lay across the shoulders of kings.

By learning about them, wearing them, and preserving them, we don’t just keep traditions alive, we remind ourselves that value is not only in what glitters, but in what holds meaning.

latest video

nia via inbox

Stay connected. Subscribe and get updated on what's new with Nia!