The Gold and Salt Economy of Medieval West Africa

The gold and salt economy of medieval West Africa refers to the extensive network of trade routes linking savannah kingdoms with North African and Mediterranean markets. Over nearly a millennium, these routes facilitated the exchange of gold and rock salt across the Sahara Desert and enabled the movement of ideas, faiths, and technologies. Control of this commerce underpinned the wealth and power of empires such as Ghana, Mali, and Songhai, shaping political structures and cultural life from roughly 500 to 1500 CE.

Origins and Early Development

Trade in West African gold predates the medieval era, with Carthaginian explorer Hanno’s fifth-century BCE voyage hinting at early contacts between the Mediterranean and the Senegal River region. Greek historian Herodotus described a cautious shoreline barter system, where locals left gold on the beach in exchange for goods before retreating, ensuring mutual safety. Although Romans exchanged luxury items such as olive oil and exotic animals through Tripolitania, it was the advent of Islam and the introduction of the camel around the eighth century CE that transformed the Sahara into a commercial highway.

Rise of Trans-Saharan Caravans and the Golden Age

The twin forces of North African Islamic expansion and the camel’s endurance turned the desert into a highway of commerce. Caravans departed salt-mining towns like Taghaza with slabs of rock salt bound for southern markets and returned laden with gold dust from the Bambuk and Wangara fields. Islamic dynasties demanded gold for coinage, luxury goods, and military payrolls, sparking a boom that made West Africa one of the world’s greatest gold producers by the thirteenth century. Salt, scarce in the savannah but essential for food preservation and human health, became nearly as valuable as gold, earning its own role as currency in Sahelian markets.

Mechanisms of Trade: Routes, Commodities, and Currency

Trade routes formed a complex web rather than a single road. Caravans navigated from Gao, Timbuktu, and Walata across shifting desert sands to Fezzan, Tripoli, and Sijilmasa. Along the way, merchants exchanged not only gold and salt but also ivory, kola nuts, leatherwork, textiles, and enslaved people. Local rulers imposed standardized tolls—often five to ten percent—on all goods passing through their territories, while gold dust was weighed against salt slabs using calibrated scales. Merchant associations and guilds organized caravan logistics, secured water points, and negotiated safe passage with nomadic tribes.

Beneficiaries: Kingdoms, Traders, and Societies

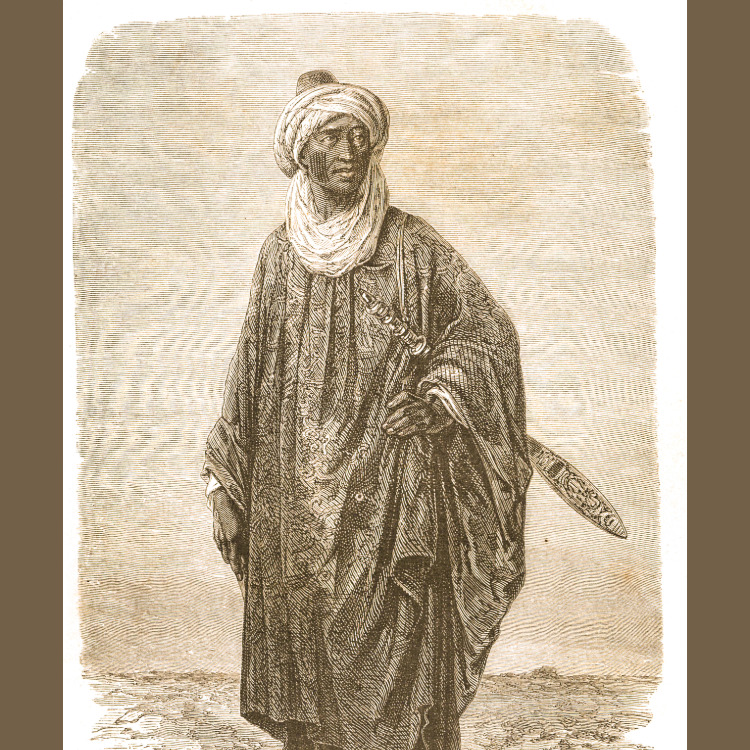

The gold-salt economy created a cascading network of beneficiaries. Kingdoms such as Ghana first institutionalized toll-gate systems, while Mali and Songhai expanded control over goldfields and caravan routes to amass vast treasuries. Urban centers grew into cosmopolitan hubs where Muslim scholars, Berber traders, and local elites converged. Caravan leaders earned fortunes transporting hundreds of camels, and artisans converted wealth into monumental architecture, manuscript libraries, and court patronage. Even nomadic tribes profited by trading desert goods—salt and ostrich feathers—in exchange for grain and textiles from the south.

Cultural and Religious Impacts

The gold-salt trade catalyzed the spread of Islam and a vibrant manuscript culture. Trade wealth funded construction of mud-brick mosques in Timbuktu and Djenné, while Quranic schools attracted scholars from Cairo, Fez, and Andalusia. Manuscripts elaborately illuminated with gold and indigo leaf testify to cross-Saharan artistic exchanges. Sufi brotherhoods such as the Qādiriyya introduced devotional poetry and communal rituals that blended Islamic orthodoxy with local traditions. The use of salt as currency—cut into standardized pieces—highlighted its symbolic and practical value in daily life.

Decline and Transformation

The gold-salt economy began to wane in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries as Portuguese maritime routes circumvented the Sahara and tapped coastal gold fields. Discovery of vast New World deposits temporarily redirected Atlantic commerce, diminishing the relative importance of trans-Saharan caravans. Internal political fragmentation, environmental shifts such as desertification, and competition from emerging Atlantic-trading states further eroded the old system. By 1600 CE, Sahelian empires had lost their monopoly over gold and salt trade, ushering in a new economic era centered on coastal exchange and European demand.

Conclusion

From its early roots in silent shoreline barter to the heights of imperial treasuries and grand mosques, the gold-salt economy defined medieval West Africa’s political and cultural landscape. It fostered urbanization, spread Islam, and linked sub-Saharan Africa with Mediterranean and Islamic worlds. Although it declined with the rise of Atlantic maritime trade, its legacies endure in the region’s cities, legal traditions, and collective memory.

Sources

- Mark Cartwright, “The Gold Trade of Ancient & Medieval West Africa” – World History Encyclopedia: https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1383/the-gold-trade-of-ancient–medieval-west-africa/

- “The Trans-Saharan Gold-Salt Trade” – Students of History: https://www.studentsofhistory.com/trans-saharan-trade

- “Driving Desires: Gold and Salt” – Caravans of Gold, Fragments in Time (Smithsonian): https://africa.si.edu/exhibitions/current-exhibitions/caravans-of-gold-fragments-in-time-art-culture-and-exchange-across-medieval-saharan-africa/driving-desires/

latest video

nia via inbox

Stay connected. Subscribe and get updated on what's new with Nia!