Kanem-Bornu & Hausa City-States: Trade, Faith, and Governance (c. 500–1500 CE)

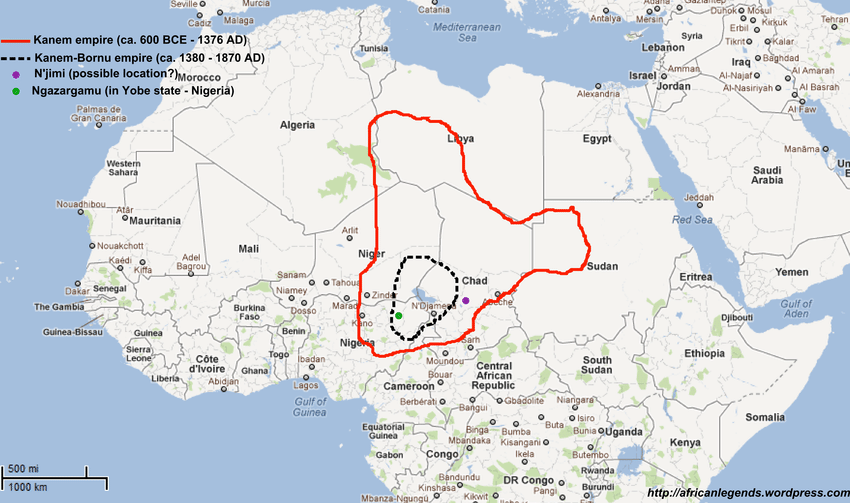

Between the sixth and fifteenth centuries, the regions around Lake Chad and the western Sudan formed a medieval Sahelian world marked by thriving commerce, evolving faiths, and innovative statecraft. Kanem-Bornu and the Hausa city-states each mastered trans-Saharan caravan routes, linking sub-Saharan resources with North African and Mediterranean markets. Their capitals—Njimi and later Birni Ngazargamu in Bornu, Kano and Katsina among the Hausa—grew into fortified hubs where merchants, scholars, and artisans converged. Through centuries of environmental shifts, dynastic change, and cultural exchange, these polities laid the groundwork for West Africa’s later empires. This article, as part of the Kingdom and Empires series, delves into their origins, institutional developments, and lasting legacies within the medieval timeframe.

Kanem-Bornu Under the Sayfawa Dynasty (c. 800–1500 CE)

The Sayfawa dynasty emerged in the ninth century around Njimi, exploiting Lake Chad’s fisheries and the surrounding savannah’s cattle pastures to build agrarian wealth. Caravans from Fezzan and Tripoli brought salt slabs and ostrich feathers into Bornu, while copper from central Sahara mines and captives from Sahel raids enriched the mai’s treasury. In the fourteenth century, Mai Idris Alooma fortified Ngazargamu with high mud-brick walls and a citadel, creating a defensible capital that controlled routes to the Nile Valley and Hausa markets. Arabic scribes and Maliki jurists joined the royal court, codifying tribute records and legal cases, which made Kanem-Bornu one of medieval Africa’s most bureaucratically sophisticated states. Despite periodic droughts and nomadic incursions, the mai maintained imperial cohesion through a network of provincial governors and mounted patrols across the desert fringes.

During its height, Kanem-Bornu balanced ritual kingship with functional administration. The mai’s throne ceremonies blended indigenous ancestor veneration with Quranic recitations, reinforcing both divine right and Islamic legitimacy. Provincial chiefs collected grain and cattle in tribute, while ghazis—mounted raiders—secured frontier zones against rival clans and hostile nomads. Caravanserais at Ngazargamu and regional waystations offered safe lodging and storage, encouraging merchant caravans to route through Bornu rather than bypass it. By the late fifteenth century, Bornu’s economy rested on integrated agriculture, pastoralism, and long-distance trade, setting a template for Sudanian statecraft that would endure into the early modern era.

Hausa City-States and Confederation (c. 500–1500 CE)

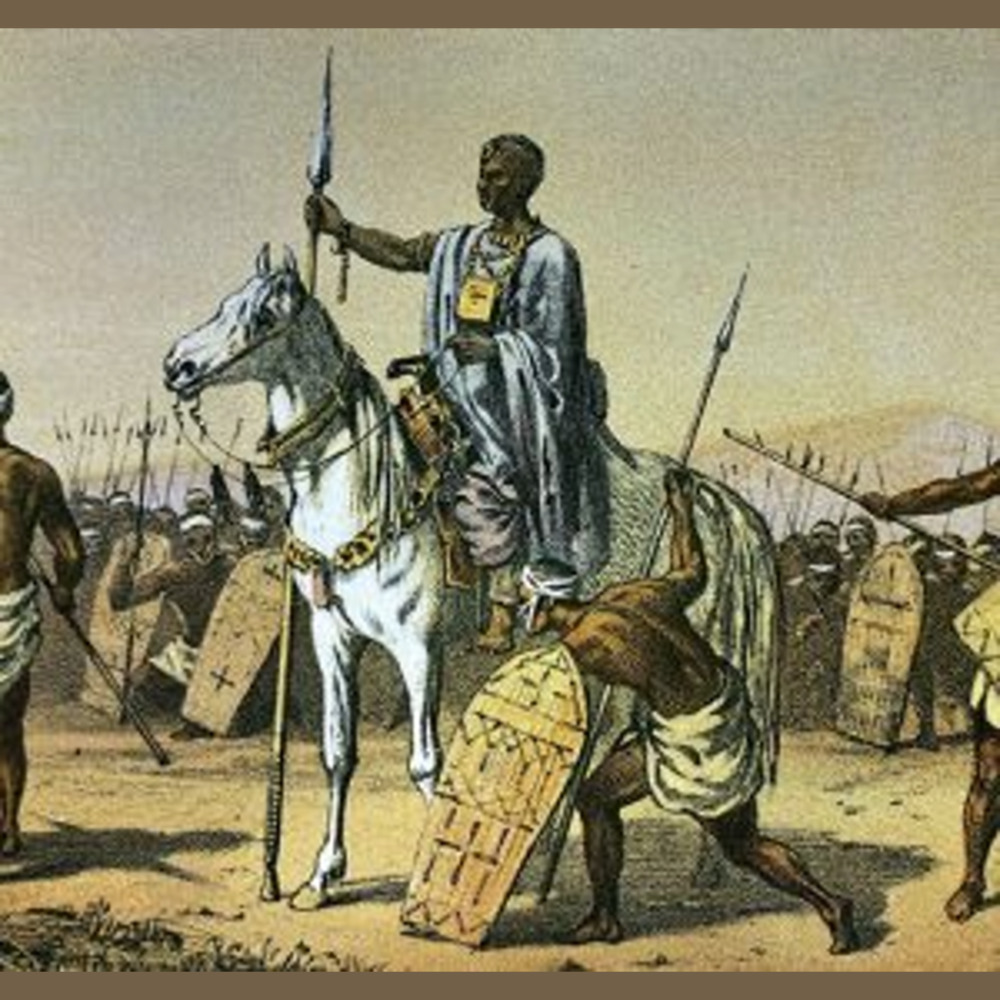

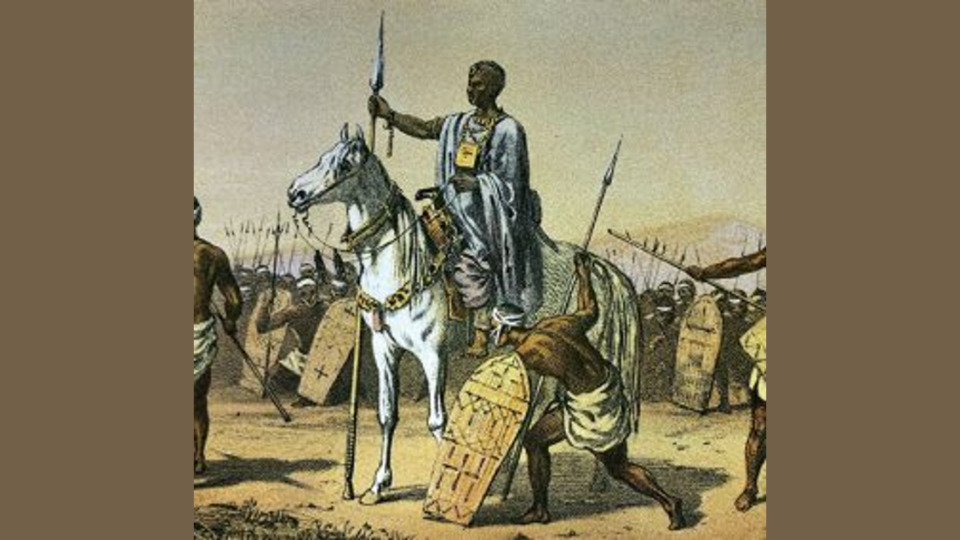

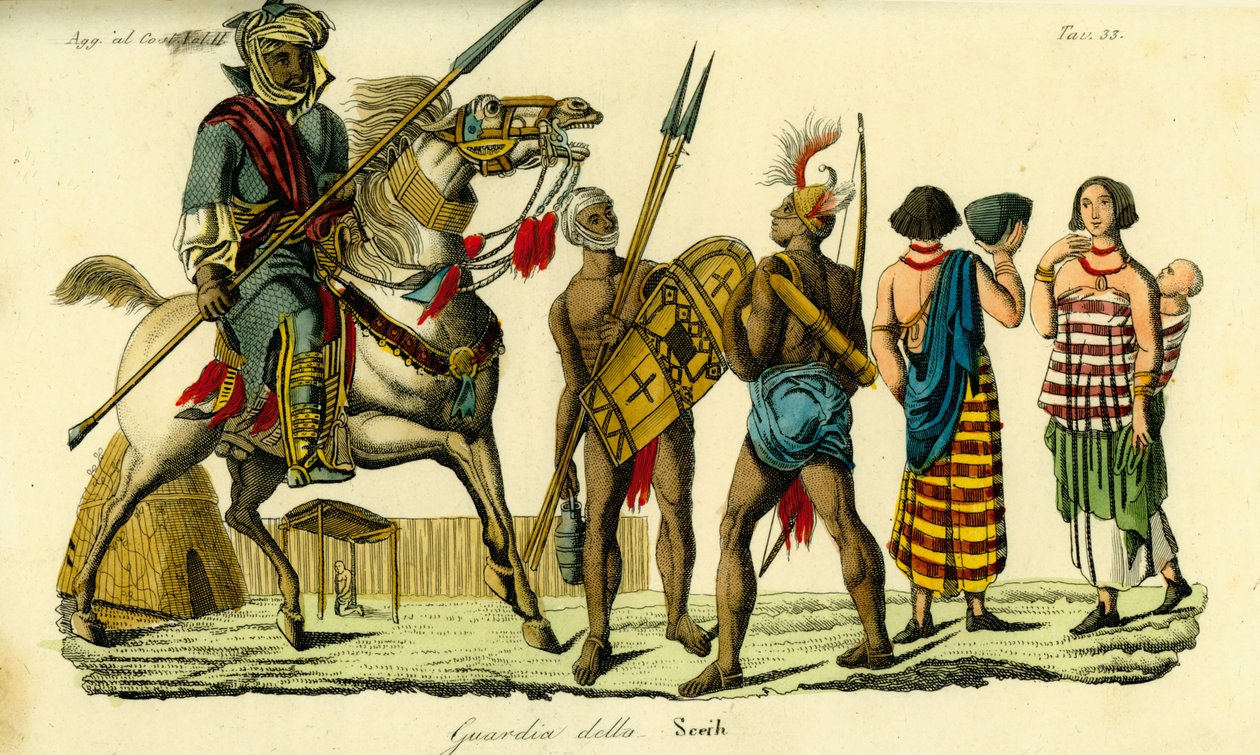

Kanem-Bornu Guard, Lancer, and Archer

Img Credit: meisterdrucke.ie - ounted bodyguard to the Sheikh of Bornu along with Kanembu lancer and Munga archer, Kanem-Bornu Empire by Unbekannt.

The Hausa polities coalesced around fertile river valleys and iron-rich uplands beginning in the seventh century, with early centers like Daura spawning offshoots such as Kano and Katsina. Each city-state built earthen ramparts—Kano’s walls reached up to fourteen meters high—to protect markets and grain stores from raiders. Political authority rested with a sarki (king) elected by a council of nobles, the Taran Kano model being the most documented, which balanced royal ambitions against aristocratic oversight. Surrounding villages produced millet, sorghum, and cotton, while cities served as nodes where trans-Saharan caravans exchanged gold dust, leather goods, and kola nuts for salt and brass ornamentation. Despite periodic rivalry, Hausa rulers formed ad hoc alliances in response to external threats, sharing intelligence and mobilizing joint defenses when caravan routes or farmlands came under pressure.

Economic specialization fueled urban growth across Hausaland. Leather tanneries near Kano’s city gate processed hides into water bags, bridles, and ceremonial regalia that bore embossed floral patterns. Blacksmith quarters produced hoes for farming, iroko-wood pestles, and spearheads for local militias, while dyers converted locally grown cotton into indigo-patterned strips. Merchant caravans, organized by gharazu (trade guilds), navigated routes to Bornu, Timbuktu, and Gao, paying standardized tolls at each city-state’s customs post. These networks knitted the Hausa states into the broader Sahelian economy and elevated city-based elites who invested in mosque foundations and Quranic schools, signaling both piety and prestige.

Religious Transformations

Artisanal guilds in Bornu and Hausaland regulated every stage of production, from apprenticeship to trade export. In Ngazargamu, copperworkers melted ingots into decorative bells and body ornaments, while cloth weavers created woolen blankets patterned with geometric motifs favored by elites. Kano’s leatherworkers developed tanning pits that used tannin-rich mahogany bark to produce water-resistant hides, sought after across the Sahel. Caravans organized by merchant associations carried these goods, along with ivory and ostrich feathers, to Fezzan and Fez, translating local craftsmanship into pan-Saharan demand. Urban markets, held weekly or biweekly, became sites of cultural exchange where Persian glass beads, North African ceramics, and West African textiles changed hands under the watchful eyes of tax collectors and qadis.

Political Structures and Administration

Kanem-Bornu’s imperial court featured a hierarchy of wazīrs (chief ministers), qāḍīs (judges), and shurṭa (military police) who maintained order across provinces known as daïras. Tribute registers, written in Arabic, documented obligations from vassal chiefs, enabling the mai to mobilize resources for military campaigns and public works. The Hausa model contrasted with its focus on consensus-building: councils of elders and guild masters convened to resolve disputes and confirm new sarakuna, leveraging customary law recorded orally by griots. While the mai projected authority through garrisoned patrols and fortified capitals, Hausa sarki reinforced their legitimacy through annual festivals, judicial pronouncements in the Friday mosque, and strategic marriage ties across city-states. Together, these complementary structures illustrate medieval West Africa’s diversity of governance rooted in local traditions and transregional connections.

End of the Medieval Era

By 1500 CE, Kanem-Bornu and the Hausa city-states had forged resilient networks of trade, faith, and political innovation that defined the medieval Sahel. Their capitals served as crucibles where African and Islamic institutions converged, producing literate courts, religious schools, and artisanal guilds unmatched elsewhere on the continent. Despite environmental pressures and shifting caravan routes, these polities adapted through administrative reforms and cultural synthesis. The legacies of the Sayfawa mai’s written archives and the Hausa sarki’s council-based governance continue to inform modern state structures and cultural identities across Chad, Nigeria, and Niger. Understanding their medieval achievements offers vital context for West Africa’s enduring dynamism.

Sources

- Kanem-Bornu | History, Map, Culture, & Empire – Britannica: https://www.britannica.com/place/Kanem-Bornu

- Kanem–Bornu Empire – Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kanem%E2%80%93Bornu_Empire

- Hausaland – World History Encyclopedia: https://www.worldhistory.org/Hausaland/

- Hausa States | History, Culture & Legacy – Britannica: https://www.britannica.com/place/Hausa-states

- Trans-Saharan Trade | Oxford Research Encyclopedia of African History: https://oxfordre.com/africanhistory/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.001.0001/acrefore-9780190277734-e-83

latest video

nia via inbox

Stay connected. Subscribe and get updated on what's new with Nia!