The Ghana Empire: Origins, Ascendance, and Decline

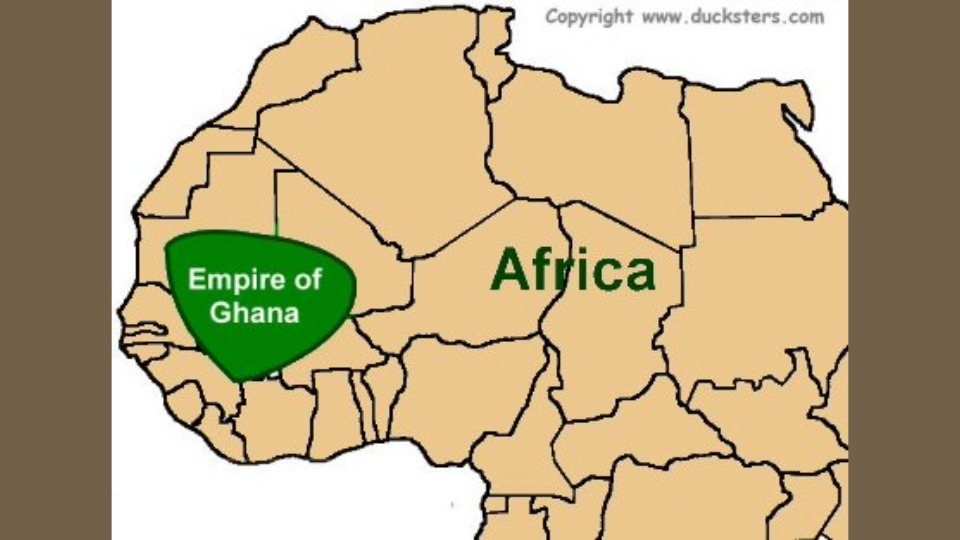

Spanning from roughly the 3rd to the 13th centuries CE, the Ghana Empire emerged as the first major Sahelian civilization in West Africa. Nestled between the vast Sahara Desert and the rich forest zones to the south, it leveraged control over gold and salt trade routes to amass unprecedented wealth and influence. With a sophisticated dual-court administration, strategic alliances with Berber and neighboring states, and a cultural tapestry woven from indigenous animist traditions and the growing presence of Islam, Ghana set the stage for later empires like Mali and Songhai. This article is the first of our Empires & Kingdoms series as it delves into Ghana’s founding in the floodplains of the Upper Niger, its golden age of economic prosperity and artistic achievement, and the environmental, political, and external pressures that precipitated its decline.

Beginnings: From Soninke Chiefdoms to Imperial Power (c. 300–800 CE)

The Ghana Empire emerged in the fertile floodplains of the Upper Niger River, where seasonal inundations deposited rich silt that sustained millet and sorghum cultivation and supported dense cattle herds, the latter underpinning social status among the Soninke clans. Straddling the edge of the Sahara and the West African forests, this region’s proximity to vast goldfields in modern-day Mali and Mauritania laid the groundwork for an economy centered on trans-Saharan trade. Political unification grew out of alliances and rivalries among Soninke chiefdoms, until one royal lineage—the Dinga—consolidated authority through strategic marriages and claims of descent from the mythical hero Wagadu. As markets in Kada and Jenne prospered with kola nuts, ivory, and leather, Soninke leaders established toll stations at desert oases, collecting duties on salt and gold and transforming a loose network of villages into West Africa’s first centralized state.

2. Golden Era Highlights: Economy, Governance, and Culture (c. 800–1100 CE)

ghanaempire01-culture

At its zenith, Ghana’s wealth rested on a finely tuned gold-salt economy. Caravans of camels carried slabs of Saharan salt northward, returning laden with gold dust that the empire standardized into kich’e units. By imposing a five to ten percent duty on each load, Ghana funneled riches into royal treasuries and financed grand construction projects. Governance mirrored this prosperity: the emperor—known as the War-Dinga—ruled from two interlocking courts. The Great Court negotiated treaties, managed tribute ceremonies, and oversaw foreign affairs, while the Inner Court adjudicated disputes, administered justice, and managed royal estates. Provincial governors, often drawn from the royal family, enforced tax collection and commanded local militias, ensuring stability across distant provinces. Cultural life in Kumbi Saleh blended indigenous animist traditions with a growing Muslim merchant class; stone mosques and Quranic schools attracted scholars from across the Sahara, while court artisans crafted intricate gold jewelry, carved wooden doors, and dyed leather goods. Griots—hereditary storytellers—preserved Ghana’s founding legends in epic oral performances, embedding the empire’s achievements into West Africa’s collective memory.

3. Decline: Fragmentation, External Pressures, and Legacy (c. 1100–1230 CE)

ghanaempire01-drought

A series of prolonged droughts in the eleventh century dealt a critical blow to Ghana’s agrarian foundation. Crop failures reduced food surpluses, cattle herds shrank, and the state’s capacity to levy taxes on trade weakened. Simultaneously, new gold deposits opened farther east, rerouting caravan traffic away from Ghanaian toll posts and draining the empire’s primary revenue streams. In this vulnerable moment, the Almoravid movement from North Africa mounted incursions into the Sahel. Driven by religious zeal, these Berber warriors disrupted established trade networks and challenged the legitimacy of Ghana’s animist leadership. Even though the initial Almoravid raids did not result in sustained occupation, they sowed instability and emboldened internal challengers. As royal authority faltered, provincial governors carved out their own fiefdoms, and rival Soninke factions engaged in succession battles that fractured the empire. By around 1230 CE, Sundiata Keita’s rising Mali state absorbed the remnants of Ghana, adopting its trade routes, administrative practices, and court rituals. Though Wagadou’s political power faded, its model of trade-driven prosperity, sophisticated governance, and religious pluralism set the template for later West African empires and continues to inform our understanding of African history today.

References

• Ghana Empire – World History Encyclopedia: https://www.worldhistory.org/Ghana_Empire/

• Ghana Empire: History, Achievements & Major Facts – World History Edu: https://worldhistoryedu.com/ghana-empire-history-achievements-major-facts/

• Ghana | History, Culture & Legacy – Britannica: https://www.britannica.com/place/Ghana-historical-West-African-empire

• Ghana Empire – Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ghana_Empire

• The Rise and Fall of the Ghana Empire – African Sahara: https://www.africansahara.org/the-rise-and-fall-of-the-ghana-empire/

• The Ghana Empire | World History – Lumen Learning: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-worldhistory/chapter/the-ghana-empire/

latest video

nia via inbox

Stay connected. Subscribe and get updated on what's new with Nia!